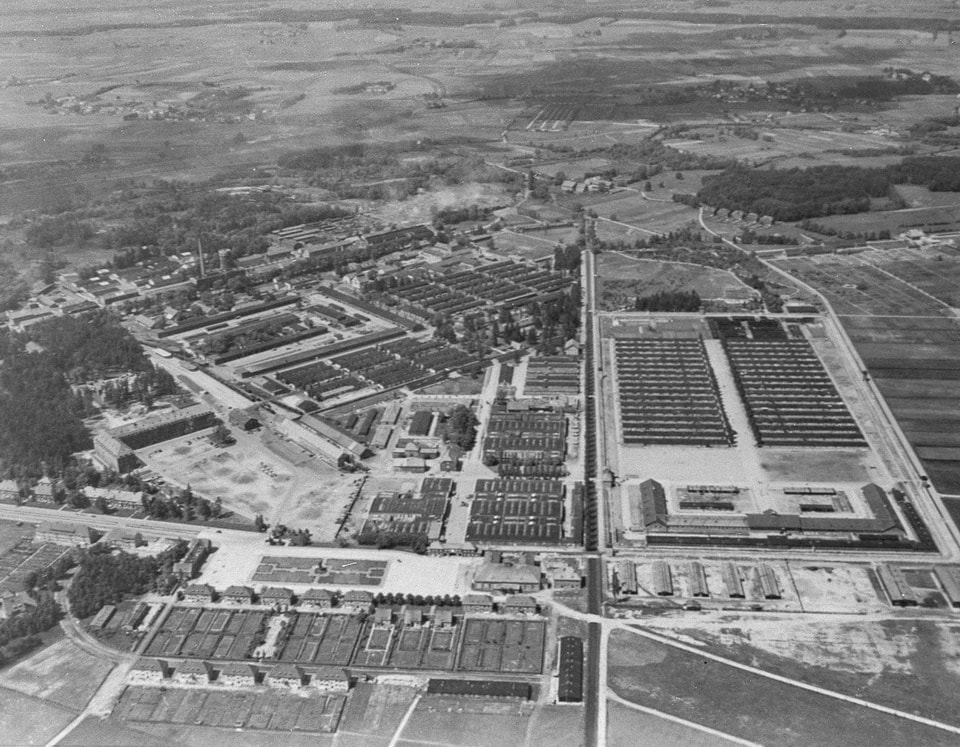

The SS had several main headquarters, some of them was located at the same place as an Concentration Camp, which was the situation with SS-Standort Dachau. For most people “Dachau” is equal to the Concentration Camp located there. And of course, the camp was first (1933) but the area was rapidly widening. And the camp was soon just a small part of the area.

To begin was the first SS unit to be located there was the unit who guarded the camp. but Eicke, who took over the camp from Hilmar Wäckerle, made the are grew very rapidly. They bought houses and area around the camp and when you look over a areal photo of the area you will see how big it was

The units who was stationed at the SS-Standort from 1933 to 1945 was the following:

Der SS-Standort Dachau 1933 – 1945

SS-Konzentrationslager Dachau 22.03.33 – 00.04.45

SS-Totenkopfverband „Oberbayern“ 00.03.33 – 00.09.39

SS-Lazarett Dachau 22.11.35 – 29.04.45

SS-Sanitätsschule Dachau 16.05.38 – 00.04.45

SS-Sturmbann „N“ 01.10.36 – 00.07.39

SS-Panzer-Abwehr-Abteilung/SS-VT 00.07.39 – 00.08.39

Waffenmeister-Vorschule 1936/37

Waffenmeisterwerkstätte 1938

Führerschule des Verwaltungs-Wesens 15.04.37 – 00.12.43

Führerschule der Allgemeinen SS 15.09.37 – ?

SS-Totenkopf-Wachsturmbann Dachau 00.09.39 – 28.04.45

SS-Totenkopf-Division 00.10.39 – 00.12.39

SS-Totenkopf-Rekruten-Standarte 00.10.39 – 00.04.40

SS-Totenkopf-Artillerie-Ersatz-Abteilung I und II, ab Juni 1940

SS-Totenkopf-Artillerie-Ersatz-Abteilung,

ab 1.1.1941 III. Abteilung SS-Art.Ers.Rgt. 24.04.40 – 00.04.41

SS-Totenkopf-Infanterie-Ersatz-Kompanie 24.04.40 – 20.10.40

SS-Standortkommandantur Dachau 06.05.40 – 00.00.00 (?)

Inspekteur der SS-Totenkopf-Ersatzeinheiten

und Kommandeur der Ersatztruppenteile der

SS-Division „Totenkopf 08.05.40 – 00.00.40

SS-Truppenwirtschaftslager TWL bzw.

SS-Haupt-Wirtschaftslager HWL München-D. 00.00.40 – 00.04.45 (?)

SS-Waffenmeisterschule 20.04.41 – 01.09.41

Waffentechnische Lehranstalt der SS 01.09.41 – 00.04.45

Ersatz-Abteilung der Wirtschafts-Verwaltungsdienste der Waffen-SS 30.03.41 – 00.04.45

Heimatverwaltung der SS-Totenkopf-Division 01.04.41 – 00.00.00

Besoldungsstelle der Waffen-SS Dachau 00.00.00 – 00.00.00

SS-Lehrküche Dachau 00.00.41 – 00.00.45

SS-Stammkompanie z.b.V. 1943

SS-Wachkompanie 7 München 1944 – 1945

1933

Through his appointment as acting police chief of Munich on March 9, 1933, the “Reichsführer-SS”, Heinrich Himmler, was given the opportunity to entrust the SS with executive tasks.

On March 15, 1933, he was appointed “political advisor to the State Minister of the Interior” and on April 1, 1933, “political police commander of Bavaria”, to whom the political police, the auxiliary police and the concentration camps were subordinate.

But already on March 13, 1933, just four days after the National Socialist seizure of power in Bavaria and Himmler’s appointment as Munich police chief, but before he took over any further offices, a commission of the political police appeared on the site of the former Royal Powder and Ammunition Factory in Dachau , which was built by the Bavarian state during the First World War, was taken over by the German Reich in 1919 and in which all mechanical systems had to be removed or destroyed due to the provisions of the Versailles Treaty.

The approximately 190 hectare property, which was spread over five communities, had been unused since 1924. There were around 200 smaller and larger buildings there.

Of the 304 buildings built during the First World War – 158 for powder operations, 146 for ammunition operations, plus 13 external buildings at the Würmmühle – around 230 were still shown on the 1933 inventory plan; Of these, around 35 were initially used by others and could only be taken over later; around 100 were slated for demolition, meaning that only just under 100 actually remained for further use.

The infrastructure – water and drainage connections, railway tracks with a connection to the Reichsbahn, bridges over streams, electrical systems and heating ducts – was still there, but like the buildings, it was neglected due to decay and destruction and in need of renovation.

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 115, see also note 2, as well as BAB R2-28350 Chronicle of the entire SS camp in Dachau, p. 1, see also Jan Erik Schulte, forced labor and extermination. The economic empire of the SS, Schöningh, 2001, p 99, note 27: BA R2-28350, Chronicle of the entire SS camp complex in Dachau, March 1, 1938, “…. Tuchel was the first to find this chronicle. For further explanation, see Tuchel, Concentration Camp, p. 124 …” Accordingly, the “Chronicle” is from March 1, 1938! Hereafter “Schulte, forced labor, p.”)

The commission found a number of buildings from the former ammunition factory to be suitable for the construction of a concentration camp. The repair and preparation work began just one day later, and on March 22, 1933, the first KL prisoners arrived, initially guarded by police units and then, after temporary instruction by police officers, by SS members.

In the following weeks, the camp was expanded to accommodate a total of 2,700 inmates.

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 116)

Himmler, in his former role as Munich police chief, announced the opening of the first concentration camp on March 22, 1933 at a press conference.

March 21, 1933

From March 21, 1933, the 2nd police force of the Bavarian State Police under the leadership of Captain Schlemmer took over security duties in the empty ammunition factory in Prittelbach near Dachau.

March 22, 1933

The first prisoners – around 150 – from the Munich prisons Neudeck and Stadelheim and from the Landsberg am Lech prison arrived in Dachau on March 22, 1933

April 11, 1933

On April 11, 1933, the SS (initially together with the police) under Hilmar Wäckerle took over guarding the camp.

May 30, 1933

Official handover of the guard management and the guard and security service from the police to the SS on May 30, 1933

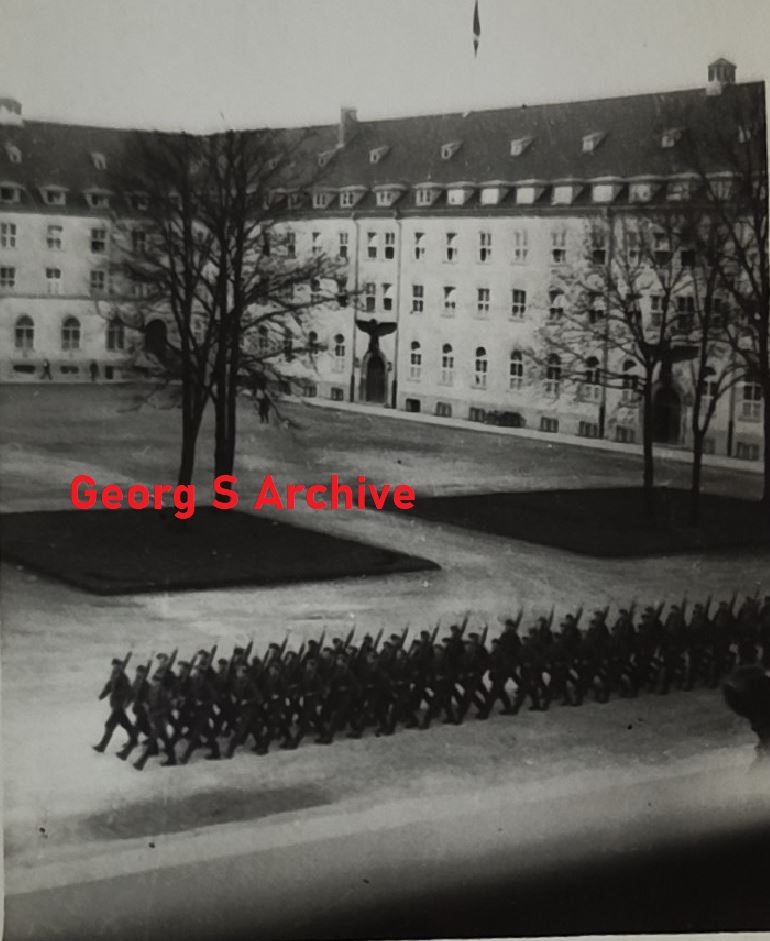

The beginnings of the future skull and crossbones standard were already in 1933 with the formation of the SS guard force “Upper Bavaria” for the Dachau concentration camp. The guard force was the first full-time SS concentration camp guard from the ranks of the General SS of the SS South Section.

The “Upper Bavarian Guard” set up by Eicke at the beginning of 1934 to guard KL Dachau initially belonged to the General SS. It was only with Eicke’s appointment as “Inspector of the KL and the Death’s Head Associations” in July 1934 that the latter were organizationally separated from the structure of the General SS.

The SS Totenkopf Standard “Upper Bavaria” emerged from the Upper Bavaria Guard Corps.

(Martin Broszat (ed.) Commandant in Auschwitz, Autobiographical Notes of Rudolf Höß, Deutsche Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH Munich, 19th edition April 2004, p.79, note 1)

Eicke took over the management of KL Dachau in June 1933 and with it the management of the guard troops!

As early as June 1933, the first commander of Dachau, Wäckerle, was replaced by Eicke.

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 116)

In June 1933, SS Oberführer Theodor Eicke took command of the Dachau concentration camp and the SS-Sturmbann “Dachau”, the guard force “Upper Bavaria” of the Allg. SS, which, in his opinion, was consistently corrupt and demoralized and consisted of 120 men. 60 men were immediately dismissed and replaced by carefully recruited new personnel. (Andrew Mollo, Vol.4 The Skull Associations 1933-45)

June 22, 1933

In the magazine “Der Bayerische Heimgarten” No. 26 of June 22, 1933, an article “A walk through the Dachau concentration camp” appeared.

(Stiftung Topographie des Grauens, Berlin, 2010. p. 159 Reprint of the magazine and the article (article author: Hermann Larcher, photographs: Sessner company) as well as photos, unfortunately very small format. The old ammunition factory was saved from decay by the construction of the camp accommodations were brightly colored and brightly colored. There were reports of the green, well-kept lawn decorated with flowers and stones in the shape of swastikas, and of the Schlageter monument. The author of the article, Hermann Larcher, wrote that the After the building has been repaired, prisoners should be used for further charitable work in the area around the camp. It is amazing what has become of these workers who were once seduced by communist agitators in such a short time. Photos showed camp facilities, prisoners at work, during marches and in the Gröner drill squad. Regarding the life of the prisoners, it was reported that they now had a regular life, good food and a roof over their heads, most were satisfied, only a few had a different opinion. The warehouse not only has short-term value, but will also “bring blessings and benefits” in the long term…)

July 10, 1933

Paul Krauss, who was born in Coburg on September 16, 1913 and was most recently SS-Hauptsturmführer, reported: “…One day volunteers were wanted for a barracked troop. That meant becoming a soldier! That’s what we young men wanted back then, if not a job, then a soldier. I was also enthusiastic about it. We young SS men,” Krauss had already converted from the Hitler Youth to the SS before 1933, “all reported ourselves, some were sent to Berlin, where the (later) Leibstandarte was set up. I and 6 comrades from my hometown were ordered to Dachau. With more than a hundred comrades from all over Bavaria, I arrived at the Dachau camp, later known as the Dachau concentration camp, on July 10, 1933.

First impression: Depressing – a long gray wall, somewhere in it an iron gate that we drove through. Behind the gate there are barracks fenced in with barbed wire, occasionally an armed guard in green fatigues. In the scorching July heat, the light gravel of the Dachau ground shimmered brightly and stung the eyes white. Dachau had been a large ammunition depot, a powder and ammunition factory during the First World War, was razed by the victors of 1918 and lay fallow for years. We newcomers were housed in an old, empty factory hall, divided into platoons and groups and given the name special training. I was a recruit!

Special training because this hundred, as the units were called at the time, only received military training. While the other units also had to provide guard duty around the concentration camp where the political prisoners were housed. Later, after the training, which lasted three months, we also had to do this guard duty – but to make it clear right from the start – not in the concentration camp. This was strictly separated from the part of the camp in which the hundreds were housed. The service in the concentration camp was carried out by SS men who belonged to the commandant’s office, not to the troops.

For us young men with our enthusiasm for everything military, the training we received was just right; we wanted to become good soldiers. We became it! Our trainers were all ranks in the Bavarian State Police and the Reichswehr who had served for 12 or more years. The officers are also all old soldiers, mostly participants in the First World War. Each of our instructors was a specialist in some type of training, in some of the weapons commonly used at the time. And us recruits? For us, no escalation wall was too high, no moat was too deep, no obstacle was too wide, no exercise was too difficult. But in order not to give rise to false impressions, I have to briefly go into details.

The training was divided into the following points:

- Sport in all areas except skiing, whereby just as much emphasis was placed on above-average collective achievements as on record achievements by individuals.

- Weapons training: Thorough knowledge and mastery of all infantry weapons in use at the time were trained. The weapons training took place under the most difficult circumstances, even in the dark.

- Combat training was trained for all types of combat in a modern war based on the experiences of the First World War. The highlight was the practice of live fire under conditions as similar to war as possible.

The training was tough, but without grinding or harassment. With the human material that the SS had at its disposal, top performance could be achieved in every area of training. There was only one thing we didn’t learn, and we couldn’t do it in 1941 either: jumping. Digging in, i.e. building positions, trench warfare. We had to pay for this with a lot of blood in the winter battles of the East.

Something else was added to the training: the ideological, the political training. It was taught by teachers who provided political and historical training, explained heredity to us and informed us about the dire consequences of hereditary diseases. They also taught us the difference between Bolshevik Communism and Nazism; That’s why there were no locked lockers in the barracked SS units. Respect for property had priority. It wasn’t stolen.

From 1934 to 1939 I trained SS men myself and later led them in the war. Never in this long time have I received orders or instructions or even given them to teach young people anything or to teach them anything other than soldiering that would have been against humanity, against international martial law, against decent views or morals. Misdeeds, riots and crimes that occurred later are in no way based on the training. There are completely different reasons for this.

The Dachau camp: As already mentioned, a former ammunition factory with a huge area surrounded by a wall. With our own experimental shooting ranges. The entire complex was demolished after the First World War. Everything lay fallow for more than 10 years…

For the purposes it was now supposed to serve, it was ideally located on the edge of the Dachauer Moos, half of which the Amper flows, and the Würm flows through it, near the city of Munich.

The camp itself was separated into two parts; the smaller part with around 10 residential barracks (1933) served as a concentration camp. The larger part was a troop camp. Our accommodations were crumbling workshops, empty machine halls, ruins. It was expanded and expanded into what it later was by the prisoners over the years.

After 12 weeks of basic training, we new ones were divided into the existing units; I came to the first hundred. From now on everyone had to take part in the usual duties, which meant guarding prisoners in addition to the more extensive military drills. I also guarded prisoners when my unit was on guard duty, including when working outside the camp. Guarding the prisoners didn’t suit us young people at all.

You need to know the following: There was a sharp separation between the concentration camp and the troop camp. The concentration camp area was separated from the troop camp by a separate fence. No member of the troops was allowed to enter the concentration camp. Exception: written approval! Contact with the prisoners was almost impossible; This only arose when prisoners had to be guarded outside the camp. But there was always someone in charge from the commandant’s office, the actual concentration camp team, there.

The powers were also sharply separated. On the one hand, the concentration camp commandant with its employees and the office of the then Bavarian political police – on the other hand, the troops with their troop commander. The difference between troop members and the actual concentration camp staff was, there is no other way to put it, like the relationship between a Bavarian state police officer and a law enforcement officer of the judiciary. Exactly and nothing else – and as far as I know, this remained the case, even though the members of the Totenkopf association were officially listed as guards.

The group! The force was made up of SS men from all over Bavaria, but there were also Thuringians and Saxons among them. Age ranges from 17 to almost 60 years. Almost all of the older ones had been soldiers of the First World War and most of them were so-called “old fighters”, in the sense of their early membership in the NSDAP and its branches, such as the SA or SS

In the true sense, it was a revolutionary group that was now to be turned into a reliable force, in the spirit of the political soldier.

The supervisors and trainers were provided by the Bavarian State Police and the Reichswehr. Himmler was acting police chief of Bavaria at the time. It was clear that such a motley crew couldn’t be turned into a disciplined team in the blink of an eye.

The men who had been in the NSDAP combat organizations before 1933, i.e. the “Old Fighters,” felt neglected because they claimed to have made the revolution and therefore had certain privileges. Even though they were participants in the war and “old fighters”, they were still unable to put together a proper force without the help of the police and the Reichswehr. Of course, some people said: “Yesterday the police beat us up, today we should listen to them and follow their orders, we won’t go along with that!”. Nevertheless, it was right to rely on the military experts from the police and the Reichswehr.

This naturally led to friction; So in the spring of 1934 there were incidents that, in a soldier’s sense, can only be described as a mutiny. The oldest among us did not want to be trained by the police. We boys, on the other hand, agreed to the tough military training. The state police major, who was responsible for training as the troop commander, was very popular with us young people, but hated by the older ones. This is how the incident occurred, which was viewed as a mutiny and almost led to the shooting of some comrades, including myself. What happened?

A Saturday afternoon, around 3 p.m. The first hundred, of which I was a part, had recently returned from a 20 km march and had been ordered to go to bed. That day I was a sergeant on duty and checked whether bed rest was being observed. After my check, I stood in front of the accommodation, everything was quiet and peaceful. The accommodation, we called it barracks, had 3 floors. On the first floor the 1st, on the second the 2nd, on the third the 3rd hundred. The 2nd was on guard duty, the 3rd was off duty.

I was standing in front of the entrance and looking over the barracks yard when the police major, our commander, drove across the yard in an open car at walking pace. Then a flower pot flew out of the window on the third floor, hitting the commander in the shoulder and shouts like “police pig” and other shouts that I couldn’t understand rang out. This was an insult and physical attack on a superior. I had seen it and heard it, but I couldn’t tell who it was, because when I looked up there were many heads at the windows from the third hundred – but who had thrown, who had shouted?

It was clear that a deserving, good officer who did his best could not accept this. Initially, a curfew was imposed and no one was allowed to leave the accommodation. Then the 1st and 3rd Hundreds had to give up their weapons; This was carried out by the 2nd hundred on guard, because they had live ammunition. There was no shooting.

The next day, SS-Gruppenführer Eicke went into action in Dachau. The 1st and 3rd Hundred had to line up without weapons and every 10th man was to be shot because of mutiny, that was the order. We stood in a large, empty hall surrounded by the 2nd Hundred, who were still on guard. Then the command was given: Count to 10, the tenth person step forward 3 steps each time, I was one of the ten. Eicke then asked: “Who else has something to say” could do it now. Then I took another step forward and said “It wasn’t a mutiny in the military sense, it was individual stupidity”; They just haven’t understood yet that the time of upheaval is over and that order and discipline must now prevail. One should not overlook the fact that we are all volunteers and anyone who doesn’t like order and discipline can go home

In any case, we boys agree with proper military training and have nothing against our superiors, wherever they come from.

Eicke then withdrew with the officers and trainers of the police and the Reichswehr to discuss. After half an hour they came back and Eicke said that the matter was settled, the troops were being reorganized, the older ones were not being sent home, they were being transferred to the concentration camp staff. But in the future, indiscipline would be punished with the utmost severity. Before Eicke arrived, the offended police officer had asked for signatures from eyewitnesses in order to be able to prove the incident. These signatures were burned in front of everyone. The case was closed and we were allowed to receive our weapons again. Although we hadn’t believed in shootings from the start, we were now very happy and relieved. The case was settled. From now on the training went uninterrupted and we young men had less to do with guarding the prisoners; We were happy about that because the security service didn’t suit us at all. …”

(I too am a witness from the century, Paul Krauß, self-published Coburg, second improved and supplemented edition, written in the first quarter of 1983, supplemented in 1991, 75 pages, pp. 22 – 27)

July 16, 1933

On July 16, 1933, a propagandistic photo report appeared in the magazine “Münchner Illustrierte Presse”, apparently inspired by Himmler. It was entitled “The Truth about Dachau” and the subtitle Early Roll Call in the Training Camp. The cover picture showed prisoners dressed neatly and cleanly. The article pointed out that every revolution eliminated its enemies: in France through the guillotines, in Russia millions through the subhumanism of the Cheka. In this way, the SA and SS would also stand unsullied before the eternal judgment of history, and the National Socialist revolution could be called a holy revolution. The enemies wanted to destroy the leader’s work. The Marxist and Jewish intellectuals abroad thought up the “vilest slanders […] about the Bavarian educational camp.” The truth is, as can be seen in the photos, that in the Dachau camp people were educated to work and discipline. They are treated strictly but humanely, they are under medical care, and they have never fared so well as in the Dachau camp, where they were finally given the opportunity to practice their jobs.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/KZ_Dachau_in_der_nationalsocialistische_Presse

By the end of 1933, improved barbed wire fencing and watchtowers were completed and numerous buildings were prepared for SS quarters and headquarters, kitchens, sick bays and other supply facilities for the guards and concentration camp prisoners. There were also various workshops.

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 116)

In Dachau, a large number of the prisoners were used to repair the buildings and carry out civil engineering work on the site.

In addition, a large number of craft businesses were established as early as 1933, especially scribes, locksmiths, tailors and shoemakers, as well as a bakery and a butcher’s shop.

Initially there had been delivery orders to Dachau companies – including 5,000 loaves of bread per week – which had already stopped in the autumn of 1933.

Despite protests from the Upper Bavaria Chamber of Crafts, the workshops were expanded and better equipped in 1934.

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 117)

The construction work was carried out both by private construction companies and by the SS; KL prisoners were used to a large extent.

In this way, within a few years, an extensive economic and administrative complex for the SS was created in Dachau, especially for its armed units.

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 122)

Through “… the repair of various factory halls as work rooms, the prisoners in protective custody were also employed as carpenters, locksmiths, tailors, shoemakers, etc….”, according to the SS chronicle of March 1, 1938 for the first year of the concentration camp’s existence .

(Schulte, forced labor, p. 99)

By 1935, a bakery, a butcher’s shop, workshops for machine carpentry, hand carpentry and painters and varnishers as well as a prison tailor’s shop, shoemaker’s shop and saddlery shop were added.

(Schulte, forced labor, p. 99)

From an organizational point of view, these companies were under the command of the KL command since the concentration camp was established. However, the technical control of these institutions was in the hands of the SS administration.

(Schulte, forced labor, p. 99, for details see the following)

With regard to the costs of the construction work per year – in millions of Reichsmarks –

1933: 0.35

1934: 1.2

1935: 2.3

1936: 1.1

1937: 4.3

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 118, note 9)

December 6, 1933

On December 6, 1933, the Austrian SS Legion, four hundred strong, was moved from the SA camp in Lechfeld near Augsburg to the Prittlbach training camp.

This training camp is a former ammunition factory that had to be razed after the First World War. A large factory hall initially served as accommodation. In 1934 and at the beginning of 1935, the individual buildings were expanded into regular, modern troop accommodation with the cooperation of all men, with each company receiving its own building.

The name of the unit changed to “Hilfswerk Österreich” and a little later to “Hilfswerk Schleißheim”.

(Otto Weidinger, Division Das Reich, Volume I, Munin, 1967, pp. 30 – 31)

1934

In March 1934, the Bavarian Prime Minister Siebert visited the camp.

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 116)

In the same year, 1934, Himmler managed to have the entire site given to the NSDAP – practically the SS – without a lease.

It was not until September 1936 that the party bought the property including the buildings for a price of 600,000 RM.

(Kaienburg, Wirtschaft, p. 117, see also Note 8 Chronicle p. 10, here it is emphasized that the party acquired the SS complex completely in 1936, on the other hand it is stated for the end of 1937 that half of the area and more than was given to the Reich half of the building’s assets belonged)

In the entire complex, the organizational and two areas,

the concentration camp and

When the SS training camp (officially opened on September 1, 1935) was divided, extensive repair, conversion and new construction work was carried out until 1938 with the help of the labor of the KL prisoners.

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 117 below – p. 188 above)

In 1934/35, several buildings for SS units, including five Austrian SS hundreds, were expanded and new barracks were built, as well as buildings for a new kitchen, dining rooms, a Unterführer’s home and an SS infirmary, streets, squares and border walls were repaired Main entrance to the training camp completed.

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 118)

Between 1934 and 1938, ongoing repair and expansion work was carried out on heating and electrical systems, water supply and sewerage systems, including the draining of ponds and swamps.

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 122 above)

March 1, 1934

On March 1, 1934, officers of the Prussian State Police took over the entire training of the “Hilfswerk Schleißheim” located in the Prittlbach training camp, which was divided into four companies.

(Otto Weidinger, Division Das Reich, Volume I, Munin, 1967, p. 31)

June 30, 1934

Paul Krauss, member of the 1st Hundred: “… But time was running out and June 30, 1934 came along – the Röhm Putsch. About 6 weeks before June 30, 1934, Röhm and his staff visited the Dachau camp and saw for themselves the level of training of the SS troops there. As head of the SA, Röhm was also in command of the SS subordinate to the SA. “A short time later, a slogan went around the camp: Something is happening; something is in the air! Nobody knew more precisely – there! One night alarm! In a short time (8 minutes at the time), the troop, the SS-Standarte “Oberbayern (Regiment, at that time still Wach-Verband I “Oberbayern”, the author), as it was called at the time, was on a field march. The team vehicles that had just been delivered rolled in, live ammunition was handed out, loaded, everything went smoothly; then step away and go to the accommodation. The next day was quiet, but from now on a hundred were in constant readiness for a field march. The service’s lockstep continued, but the rumor remained. A few days later, it was at the beginning of the summer vacation, holiday break! Why? Nobody knew, the tension rose. Rumors were circulating. There is war with France, the Reichswehr wants to stage a coup. The next day the holiday ban was lifted, everything was as usual. This went on alternately until June 28th, then all bans were lifted. We were able to go out again and go on vacation. On June 28th I wanted to go on vacation and came to Dachau train station. We were several vacationers and were really looking forward to the vacation, but the joy It was short, because the counter clerk at the station said: “I’m not allowed to give you tickets; “You all have to go back to the camp immediately!”. So back – goodbye to vacation!

The barracks are on alert. Unpack your suitcase, pack your knapsack. Only the most necessary guards were left in the camp, everyone else was on alert in the quarters. We no longer made any assumptions, as soldiers it was clear to us that we were marching against whoever – if Hitler gave the order, then we would fight, whoever the enemy might be.

We were convinced of our training, also of our combat value and the spirit of the troops was outstanding. The force was at this point, despite the short period of time it existed, a fully operational instrument for civil war-like fighting. The commander at that time was Eicke. He had the absolute trust of the troops. He had it as a socialist, soldier and comrade: this never changed until his death in front of the enemy.

The night of June 29th to 30th, 1934 brought a resolution to the tension: the alarm went off at around 3 a.m.! In a short time, the 1st SS-Totenkopf-Standarte (Wach-Verband I) “Oberbayern” lined up in front of the vehicles in a field march under arms. The first rays of the rising sun were reflected in reflections on weapons, helmets and equipment as Eicke spoke to the troops: “Comrades! Traitors want to eliminate our beloved leader, want to stage a coup and sell our newly reborn Germany to a foreign power! They have gathered armed forces for this purpose! We’re moving out! “When the order to fire is given, we fire, regardless of whether a brown shirt or another is in the line of sight!”. These words of Eicke are historic.

Then the command sit up! We rolled towards Munich to the sounds of the band. We thought it was about Austria. … But things turned out differently. The column of the SS Leibstandarte joined us in front of Tölz.

We were ordered back to Munich and on the evening of June 30th we marched past Hitler, who was standing on the balcony of the Brown House. Contrary to his custom, he did not raise his hand in greeting, but stared darkly down at us. The streets were deserted, the few passers-by we saw shyly crept along the walls of the houses.

That night we were on standby with pioneers from the Reichswehr in their barracks. The state of emergency was declared. There were heavily armed Reichswehr posts at all important points and buildings in Munich, armored trains were under steam – everything pointed to revolution. But none of us, including the Reichswehr officers, knew what was actually going on.

Until the next day we received an order to disarm the SA units on Oberwiesenfeld and all SA guards in Munich, including the SA pioneers in Deggendorf. Resistance can be broken with weapons. It took around a day, then around 1,000 SA were on Oberwiesenfeld and all SA guards in Munich were disarmed. The same thing happened to another part of our troops in Ingolstadt and Deggendorf. Around 3,000 SA men are said to have been under arms in Ingolstadt. The whole thing passed without a shot being fired; the SA men offered no resistance. A week later we were back in the camp, where we learned the following from daily orders and troop roll calls: Röhm had to defeat the strong SS garrison in Dachau if his putsch was to succeed. For this purpose, he armed his SA, especially in Bavaria, and gathered them in key areas. …

Five days later, SA Standartenführer Uhl from Ingolstadt and 14 other senior SA leaders were summarily shot in the Dachau camp for betraying the leader.

In addition to the necessary guards for the concentration camp, the entire Dachau unit, including the officers and non-commissioned officers from the Bavarian State Police who were training us, as well as some commissioners from the Bavarian Political Police, lined up on the small firing range in an open square. Standartenführer Uhl and his men stood to the right of the bullet trap, and the firing squad stood in the middle of the square. None of the delinquents were tied up or otherwise disabled. Then there was a dull roll of drums and Eicke called out Uhl and his men one by one. First Uhl! Eicke took a stick from the floor and said loudly and audibly: “Standartenführer Uhl, you are sentenced to death by shooting for betraying the Führer and Germany!” Then he broke the stick in two and threw it at Uhl’s feet. “If you are ready to die, then free your upper body and step towards the bullet trap!”. Then the volley rolled – 15 times!

After the second man was shot, an officer from the state police went to Eicke and asked loudly and everyone could understand: “Is what is happening here legal, has a court or a military tribunal convicted these men?” Eicke’s answer: “It is the order of the Hitler then announced a few days later: “Everything that happened during the putsch by the police, the SS or the Reichswehr was legal!”

The volley cracked fifteen times! Those doomed to death saw their comrades fall; no one showed weakness or asked for mercy. Uhl himself shouted as he stood in front of the bullet trap: “Long live the Führer!” The others: “Long live Germany”, “Heil Hitler” or “For my fatherland”. They were men! Whatever they wanted, they died free and upright, as befits men. I was saddened by the deaths of these men, as they were SA comrades. In my heart was “Germany could have used them!”. The man next to me looked at me and said: “Then they would have shot us”. “Maybe,” I said, “but that’s not certain!” Then Eicke said: “If someone had asked for his life, he would have been pardoned.”

Days later, when the waves of the putsch had subsided, a final troop roll call about the Röhm affair took place. Eicke literally said that he personally shot Röhm in his cell in Stadelheim prison because Röhm refused to shoot himself with the pistol he was given in order to draw the consequences of his betrayal. He loaded the pistol with one shot and was given 24 hours. Also shot in Dachau during the Röhm Putsch was Dr. Gustav Ritter von Kahr. Von Kahr, monarchist, was the founder of the Bavarian Home Guards and district president of Upper Bavaria from 1919 to 1921 and was definitely an opponent of any attempts at overthrow. On November 9, 1923, he was State Commissioner General of Bavaria and was responsible for suppressing the Hitler putsch. …

A few weeks later we were alerted again. But only two hundred moved out. One to Passau, one to Freilassing. There was turmoil and civil war in Austria, we stood with rifles on the banks of the Inn and had to watch as the Dollfuß soldiers shot at their compatriots who wanted to escape through the Inn to us.

The uprising (of the Austrian National Socialists) had failed; a lot died after being shot in the waters of the Inn. Many got through or otherwise reached German soil. They were housed in the Dachau camp and later formed the Austrian Legion. …”

(I too am a witness from the century, Paul Krauß, self-published Coburg, second improved and supplemented edition, written in the first quarter of 1983, supplemented in 1991, 75 pages, pp. 27 – 31)

On June 30, 1934, during the so-called “Röhm Putsch”, the “Hilfswerk Schleißheim” was also ordered to Bad Wiessee on Reichswehr vehicles, but was stopped on the way by the commander of the LSSAH, Sepp Dietrich, and put on standby to the I.R. 19 ordered back to the List barracks in Munich. It was no longer used.

(Otto Weidinger, Division Das Reich, Volume I, Munin, 1967, p. 31)

October 00, 1934

The Sturmbann “Hilfswerk Schleißheim” in the Prittlbach training camp was incorporated in October as the II. Sturmbann of the SS-Standarte 1 Munich and was given the troop designation II./1. It remained in the camp until the summer of 1936

(Otto Weidinger, Division Das Reich, Volume I, Munin, 1967, p. 32)

1935

In 1935 a parade ground – the “Reich Treasurer Schwarz Square” – was laid out in front of the gate,

an SS headquarters building with a detention wing,

a clothing store with workshops,

an SS team home for leisure activities with a canteen,

a training building,

storage rooms for food,

a weapons workshop,

Material storage for weapons and equipment,

cattle stables,

building materials warehouse,

Apartments and accommodations have been prepared for employees of commercial enterprises.

In one of the largest building complexes, the “Holländerhalle”, garages and car workshops as well as material warehouses were built in the same year,

a gas station,

a riding arena and stables for 100 horses,

a blacksmith shop,

a parade hall, as well

a material warehouse for the SS accommodation administration.

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 118)

From the summer of 1935 onwards, buildings were built again for the Totenkopf units, which the Reichsführer-SS opened in March 1936.

another barracks (new building),

a kitchen for 1,200 SS personnel along with a dining room,

a kitchen for SS leaders,

Corresponding team, sub-leader and leader quarters with canteen

and other facilities, bathrooms, hairdressers, rooms for single SS leaders and administrative offices.

(Kaienburg, Economy, p. 118)

Furthermore, around this time, the gatehouse at the KL gate was expanded into an entrance building with SS accommodation and a large equipment warehouse for clothing and other supplies was set up as a central procurement warehouse for the entire SS.

(Kaienburg, Economy, pp. 118 – 119 above)

March 18, 1935

On March 18, 1935, a new era began for the guard troops, externally visible through the awarding of a skull as an insignia on the right collar tab.

Furthermore, the previous Dachau guard force will be given the new unit name “Upper Bavaria”. The head of the SS main office also ordered that all barracked assault units of the SS guard units be numbered 1 – 25. This is intended to underline the uniform connection between all guard units.

The process of designations and numbering was not completed until June 1935.

(van Dijken, Totenkopf, p. 129, 130: June 17, 1935 still old names, new numbering proven for the first time on June 26, 1935)

Author: Roland Pfeiffer, some images Georg Schwab Archive

Part 1 finished

Sources: (Hermann Kaienburg, The Economy of the SS, Metropol-Verlag Berlin, 2003, pp. 114 – 138, here p. 114/115, note 1, after Tuchel, concentration camp, p. 121 f, hereinafter “Kaienburg, Economy, S.”)